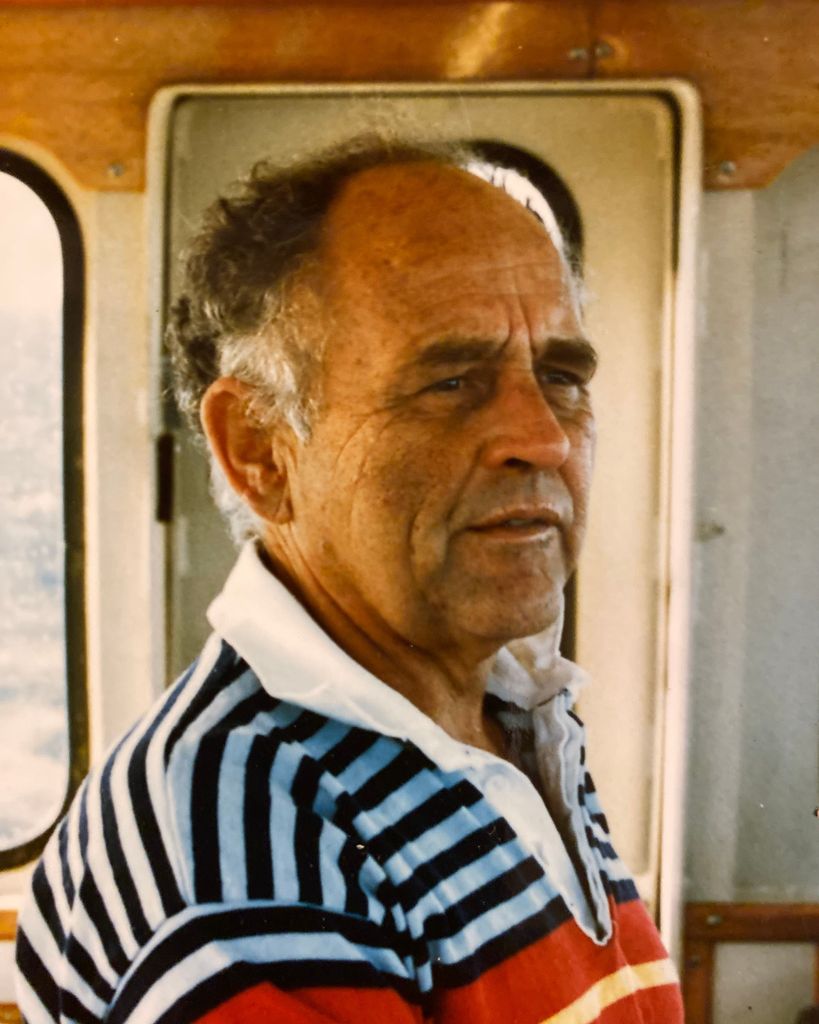

Dennison K. Breese

September 7, 1935 — November 26, 2023

Beaufort

Dennison “Denny” Breese, a man who made himself at home in the sea, as a shipwreck diver, deep ocean explorer, engineer, and inventor, and who, as a young sailor in the U.S. Navy, was a crew member on the USS Nautilus, the world’s first nuclear-powered submarine, as it made history in 1958 by sailing under the Arctic ice to the North Pole, died on November 26, 2023 in Beaufort, N.C. He was 88 years old.

Having discovered a passion for the water as a child growing up in southern California, Denny Breese spent a lifetime seeking adventures that would take him to the hidden depths of the ocean. But he was far more than a diver. His boundless curiosity and passion for discovery and for finding engineering solutions to seemingly unfathomable underwater challenges earned him a reputation as a creative problem-solver and a sought-after crew member on countless ocean expeditions.

A lifetime of deep-sea adventures worthy of a Jules Verne novel began with his four-year stint on the crew of the USS Nautilus (SSN-571). Breese joined the Navy in January 1955 and immediately was sent to submarine duty. In July, he joined the Nautilus’s original crew, embarking on a journey that culminated with a top-secret mission that would shock the world.

In the summer of 1958, the submarine left its base in New London, Conn., and sailed south to the Panama Canal and into the Pacific Ocean where it docked at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. The ship, with 116 crew members aboard, then made stops along the West Coast up to Seattle. When the Nautilus departed Seattle, the crew thought the ship was heading home, but Captain William R. Anderson informed them they were heading north to the Arctic. The covert mission, nicknamed “Operation Sunshine,” would take the Nautilus 1830 nautical miles under the ice-covered mass to the North Pole, and then on to the Atlantic Ocean. No ship had ever been able to reach the North Pole due to the deep-packed ice of the Arctic Ocean. A first attempt had to be aborted, but a few weeks later, the second voyage succeeded.

Denny Breese, at 22 years old, was the ship’s Electronics Technician. With the U.S. deeply immersed in the Cold War with the Soviet Union, the Nautilus’s mission was crucial to advancing America’s submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) weapons system. It had been personally approved by President Dwight Eisenhower. On August 3, 1958 the Nautilus reached the geographic North Pole and the jubilant crew celebrated.

Breese, embracing the moment, wrote a hasty letter to his brother Nick and put it in an envelope stamped with a special North Pole dateline created for the mission.

“This will be short,” Breese wrote to his brother in Chula Vista, California. “I just found out the mail is leaving the boat in 15 minutes. I just want you to get this envelope that was stamped from the North Pole.” Sending mail from the North Pole proved daunting. The letter was lost in transit and went undelivered for more than three decades. Incredibly, it was eventually delivered in November 1990, 32 years after it was mailed. The U.S. Postal Service couldn’t explain where the letter had been all those years. But the story made it into the New York Times and newspapers across the country.

“That was a pretty exciting event,” said Breese’s crewmate William Gaines about the mission. “We realized we were the first ones to do it. Only one can be the first.” Breese and his crewmates received the Presidential Unit Citation from President Eisenhower for heroism for their historic achievement, the first such award in peacetime, and the officers and crew were honored with a tickertape parade in Manhattan.

“Denny was extremely popular, the cool kid from Southern California,” Gaines recalled. “Everybody enjoyed him.” An innovator, Breese recruited a group of crew members and taught them how to scuba dive. The group was dubbed “The Sea Suckers.”

After his experience on the Nautilus, Breese’s post-Navy career was marked by a series of pioneering efforts in deep ocean diving and research. A history buff, he indulged his childhood dream of finding hidden treasure by locating and diving on shipwrecks. Everything about the burgeoning industry of ocean exploration intrigued him. He was present at the advent of an era of record-breaking deep dives requiring innovative submersibles and technology.

In the mid-1960s, he was a crew member on the experimental aluminum submarine, The Aluminaut. He was on board when the Aluminaut broke the world’s depth record for submarines by diving to a depth of 6000 feet, well over a nautical mile.

In 1966, he was part of the Aluminaut crew that recovered an unarmed hydrogen bomb that had been lost in the Mediterranean Sea off the coast of Spain when a U.S. Air Force B-52 bomber collided with a tanker during a mid-air refueling. The search took two and a half months.

In the late 60s, working for Ocean Systems, Inc., he was one of two divers on the Deep Diver, a deep-sea scientific research submersible designed by Edwin Link as part of his famed “Man-in-Sea” exploration initiative. The first such vessel designed for “lockout” diving, it allowed divers to leave and enter the craft while underwater. With Breese on board, the Deep Diver set a depth record for open ocean dives, and Breese worked outside the vessel at a depth of 700 feet to collect biological samples and make research surveys with biologists from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. He was featured in a 1968 National Geographic article about the Deep Diver.

In 1970, he joined Perry Oceanographics and helped develop the Hydrolab, an underwater habitat for air saturation diving for marine science. Breese spent more than a decade designing, constructing and operating advanced diving saturation systems.

Always eager to find treasure, Breese located shipwrecks in the U.S., Bermuda, the Bahamas, and Turks and Caicos. Using an underwater metal detector he developed, he helped treasure hunter Mel Fisher locate the bulk of gold, silver and jewels of the Spanish galleon Nuestra Senora de Atocha, which held treasure worth upwards of a half billion dollars. The ship, which sunk in a hurricane off the Florida Keys in 1622, was named the most valuable shipwreck ever to be recovered. Breese was paid seven years later in silver bars and gold coins.

“Denny was technically very creative about how to approach shipwrecks,” said William Mathers, who shared a background in treasure hunting and marine construction with Denny. “He was always incredibly positive, both spiritually and from a technical point of view.”

Word of his prowess spread and Breese was recruited to work as a dive safety coordinator with famed underwater cinematographer Al Giddings on Hollywood films such as The Abyss, directed by James Cameron, and The Deep, based on Peter Benchley’s novel.

The multifaceted Breese viewed every obstacle as an opportunity. Living on the coast of North Carolina in Beaufort, he owned a dredging company for which he designed and patented his Seadozer dredge with which he dredged the sand and installed 3000 feet of storm drains in the surf of Myrtle Beach, South Carolina. He worked on shore erosion projects around the world.

A joyful, caring and loving man, Breese was an iconoclast who marched to the beat of his own well-crafted drum. He lived for a time on a boat he built himself. He avoided eating fish or seafood because he so loved and respected the creatures of the ocean.

“He was always trying to solve the world’s problems,” Kara Breese said about her father. “When the nuclear power plant accident occurred in 2011 in Fukushima, Japan, he designed a solution to the crisis and did everything he could to connect with the Japanese government. He was frustrated that he couldn’t get them to listen.”

Dennison Kidder Breese was born on September 7, 1935, in Manhattan, Kansas to Reuben Breese and Kathryn (McConnell) Breese. Breese was one of four children. The family moved to La Jolla, California when Denny was a child and he grew up spellbound by the nearby ocean.

He began diving when he was 12 and built his first underwater camera at age 14. He joined the “Sea Spooks” diving club in nearby Chula Vista, where he went to high school, graduating in 1953. Though he never attended college, Breese was a voracious lifelong reader of history and other non-fiction and knew from an early age that he would spend much of his life underwater.

Breese had two children, Christopher Gove and Denise Gove, by his first wife, Patricia Reynolds, and two daughters, Willa “Birdie” and Kathryn “Kara” Breese, by his second wife Willa Breese. He is survived by his sister, Virginia “Ginny” Tinkle, by Patricia and Willa, by his four children and by his granddaughter, Alyson Gove.

His former wife, Sun Daniel, cared for him as he battled illness and she and his nephew Mike were by his side during his final days.

“His bookshelf was stacked with maritime and wartime non-fiction history books, underwater medical books, along with poetry and cookbooks,” said his daughter Willa Breese. “It illustrated his remarkable curiosity, free spirit and authenticity. He was who he was and his passion for life was boundless.”

A celebration of life will be held in early 2024.

Arrangements by Munden Funeral Home, Morehead City, NC.

Guestbook

Visits: 469

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the

Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Service map data © OpenStreetMap contributors